|

Coach

house and stables, including a cottage for the head groom (right), and a

forge, presumably for a local farrier. Subsequently, the stabling was

converted to garages and a conservatory after about 1948. The original

roofline in the foreground was obliterated in 2022, by the then

owners/developers. Changing the character of the equine complex and

potentially altering the open

market property value.

Worldwide,

transportation

before 1890 was by riding horses, unlike Comanche American Indians, using saddles, or by

hitching trained animals to drawn carts, coaches and carriages. Thus

stables were very important to any business, farm and large manor

houses. Including the supply

of hay bales (a hayloft) to feed the animals,

and straw for bedding and to absorb waste from the animals during

'mucking out.'

At

the turn of the Century, the Manor was producing vegetables and (it is

believed) exporting flavored bottled water.

The vegetables were sold locally at Hailsham and Hastings Markets.

The transition from horse-drawn transport to motorized vehicles began in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The introduction of the motor car and

engine driven bus around the 1890s marked the start of this

shift, alongside the swing from gas lighting to electrical light bulbs

as per Thomas

Edison and Joseph Swan. By the early 20th century, motorized vehicles became more common, and by the 1920s and 1930s, they had largely replaced horse-drawn transport for most purposes.

Similar to the introduction and acceptance of generating stations.

In urban areas, the change was more rapid due to the need for efficient public transport and

the rapid delivery of goods in a faster moving commercial world. Rural areas saw a slower transition, with horse-drawn vehicles still in use for some time.

In

Lime

Park, The Baron de Roemer had purpose built stabling and a forge for

a farrier, to include a coach house to keep his coach(es) and carts dry. He would have

employed

a blacksmith and grooms. And a coach builder at some point, possibly a

local man to keep his coach or carts in good order. Where deliveries of coal

were originally by horse drawn carts. As a modern innovation, Charles

de Roemer had his Armstrong

Sideley; and the family had a chauffer full time.

Behind

his stables, Charles built his electricity

generating utility, quickly expanding the enterprise to supply the

village with street lighting and power for

cooking.

Eventually,

around or after 1948, the stables and coach house were converted to a

residential use and garaging, becoming 'The Rectory,' and when sold on by the

Church

(Diocese of Chichester),

renamed; 'The Old Rectory.' Tending to confuse people as to the origins

and purpose of the buildings. Suggestive of religious beginnings, since

there are two churches in Church

Road and Chapel Row.

Between

2021 and 2023, the new owners of 'The

Old Rectory,' converted the last remaining stables and Forge, to

residential use, as ancillary accommodation. The passing of an age and

obliteration of almost all evidence of what was a unique time-capsule of

an era just outside the village of Herstmonceux.

One day these changes may be undone, perhaps if and as Lime Park

becomes a Conservation

Area, as part of a larger heritage restoration proposal. One shining

light in that respect being the Preservationist, Beatrix

Potter, who used her income from the sales of her famous children's

stories to protect her beloved Lake District. She bought land and farms to protect them from developers and managed

these properties herself, before leaving it to the National Trust when she died.

Miss Potter is thus a shining beacon, role model, and inspiration to our

Trustees.

For example, during

these conversion works, what was a square,

has been extended on the east facing wall, now protruding some twenty

feet approximately into the grounds towards the A271.

Incongruous to say the least, after consideration of the importance of

preserving evidence of our past for future generations, and a radical

departure from the original design and purpose of these (would be)

historic buildings.

We

wonder if permission of the Bishop of Chichester may have been needed

for such 'extension' works, as it appears to be required when selling

on, concerning continued use of the name: "The Old Rectory,"

though what terms and conditions remain unclear. Perhaps, more

correctly, the property name should reflect its origins: "The Old

Stables."

The good news being that at least the archaeological

evidence is recorded in a series of photographs taken during the

demolition and building

works; should Conservation Designation not take place. Funding of

restoration works being hard to come by. And likely to involve taking

down of the new sections, as restoration to the original specification

takes place. Of course, a blue-sky aspiration for those among us who are

conservation minded: Preservationists.

Who

has ever heard of a Bakery with electric machinery when horse drawn

deliveries were the norm? Herstmonceux had electricity well before most

large towns, because of Major Charles de Roemer, who also manufactured

seaplanes for the British Admiralty (Royal Navy) in Eastbourne, from

1911 to 1924. The development of harnesses to allow a horse to

comfortably pull a carriage took place over hundreds of years. The

design of the collar mostly transferring the pulling effort to forward

motion, while the belly harness brakes a vehicle.

A horse collar is a part of a horse harness that is used to distribute the load around a horse's neck and shoulders when pulling a wagon or plough. The collar often supports and pads a pair of curved metal or wooden pieces, called hames, to which the traces of the harness are attached. The collar allows the horse to use its full strength when pulling, essentially enabling the animal to push forward with its hindquarters into the collar. If wearing a yoke or a

breast collar, the horse had to pull with its less-powerful shoulders. The collar had another advantage over the yoke as it reduced pressure on the horse's windpipe.

From the time of the invention of the horse collar, horses became more valuable for plowing and pulling. When the horse was harnessed in the collar, the horse could apply 50% more power to a task in a given time period than could an ox, due to the horse's greater speed. Additionally, horses generally have greater endurance than oxen, and thus can work more hours each day. The importance and value of horses as a resource for improving agricultural production increased accordingly.

As motorized vehicles became more prevalent, the fate of redundant stables,

horses, and the people who worked with them

varied.

STABLES AND HORSES

Many stables were

re-purposed for other uses, such as garages for the new motor vehicles, storage facilities, or even converted into residential or commercial spaces.

Some horses were sold to rural areas where they were still needed for farming and other tasks. Others were relocated to riding schools, leisure riding, or even retired to pastures.

The overall population of working horses declined significantly as they were no longer needed in large numbers for transportation.

STABLE

HANDS AND GROOMS

Transition to New Roles: Many stable hands and grooms transitioned to new roles within the emerging automotive industry, such as mechanics, drivers, or working in garages.

Employment in Other Sectors: Others found employment in different sectors, including

agriculture, construction, or service industries.

Skill Adaptation: The skills of stable hands and grooms, such as animal care and maintenance, were sometimes adapted to new roles involving machinery and vehicles.

The transition was gradual, and while it brought about significant changes, many people and facilities found ways to adapt to the new technological landscape.

The transition to motorized vehicles also had a significant impact on carriage makers and blacksmiths:

CARRIAGE MAKERS

Many carriage makers adapted their skills to the burgeoning automobile industry. They began manufacturing car bodies and other components, leveraging their expertise in craftsmanship and design.

Some carriage makers diversified their businesses to include other forms of transportation, such as bicycles and early motorcycles, or shifted to producing different types of goods altogether.

BLACKSMITHS

Blacksmiths often transitioned to roles in metalworking and mechanics, using their skills to work on the new motor vehicles. This included tasks like forging parts, repairing machinery, and eventually working in

automotive repair shops.

In rural areas, where the transition to motorized vehicles was slower, blacksmiths continued to be in demand for shoeing horses and repairing farm equipment.

Some blacksmiths specialized in creating ornamental ironwork, tools, and other metal goods, finding new markets for their traditional skills.

Overall, while the shift to motorized transport brought challenges, many carriage makers and blacksmiths were able to adapt and find new opportunities in the changing landscape.

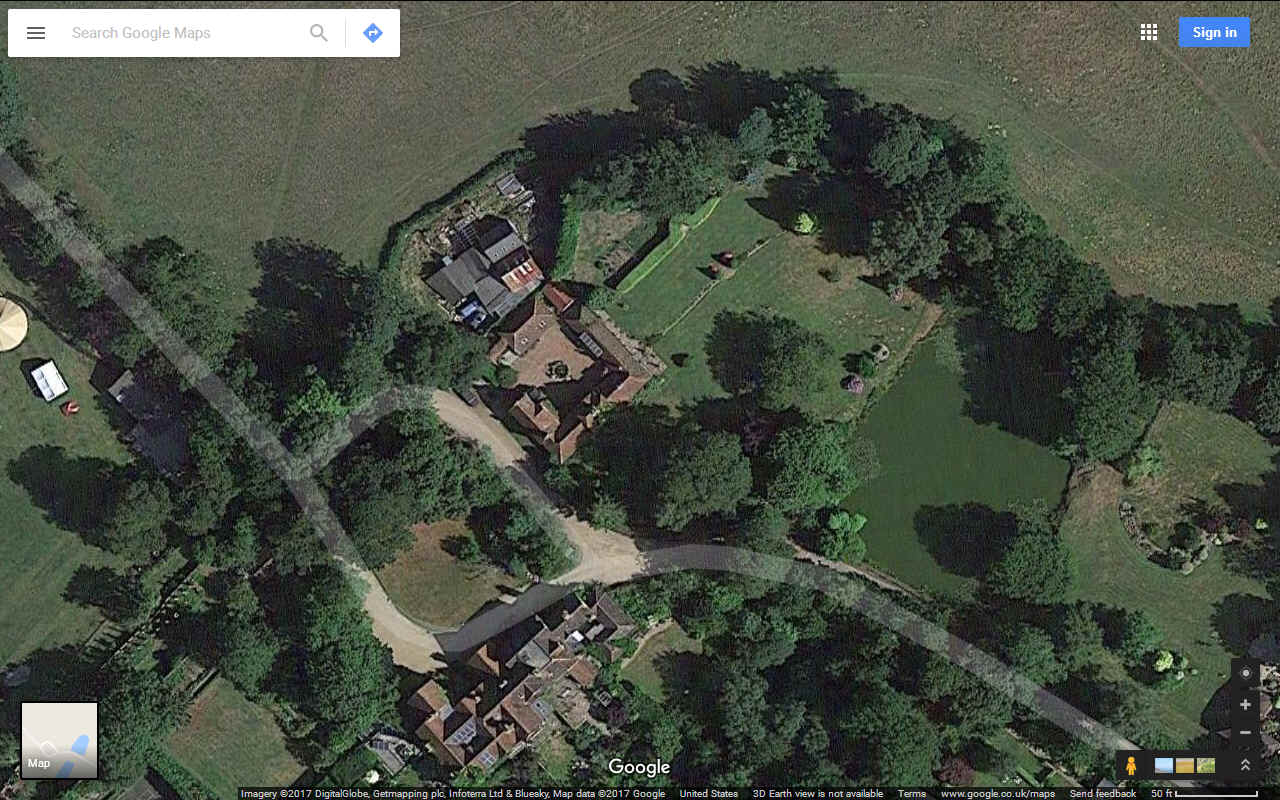

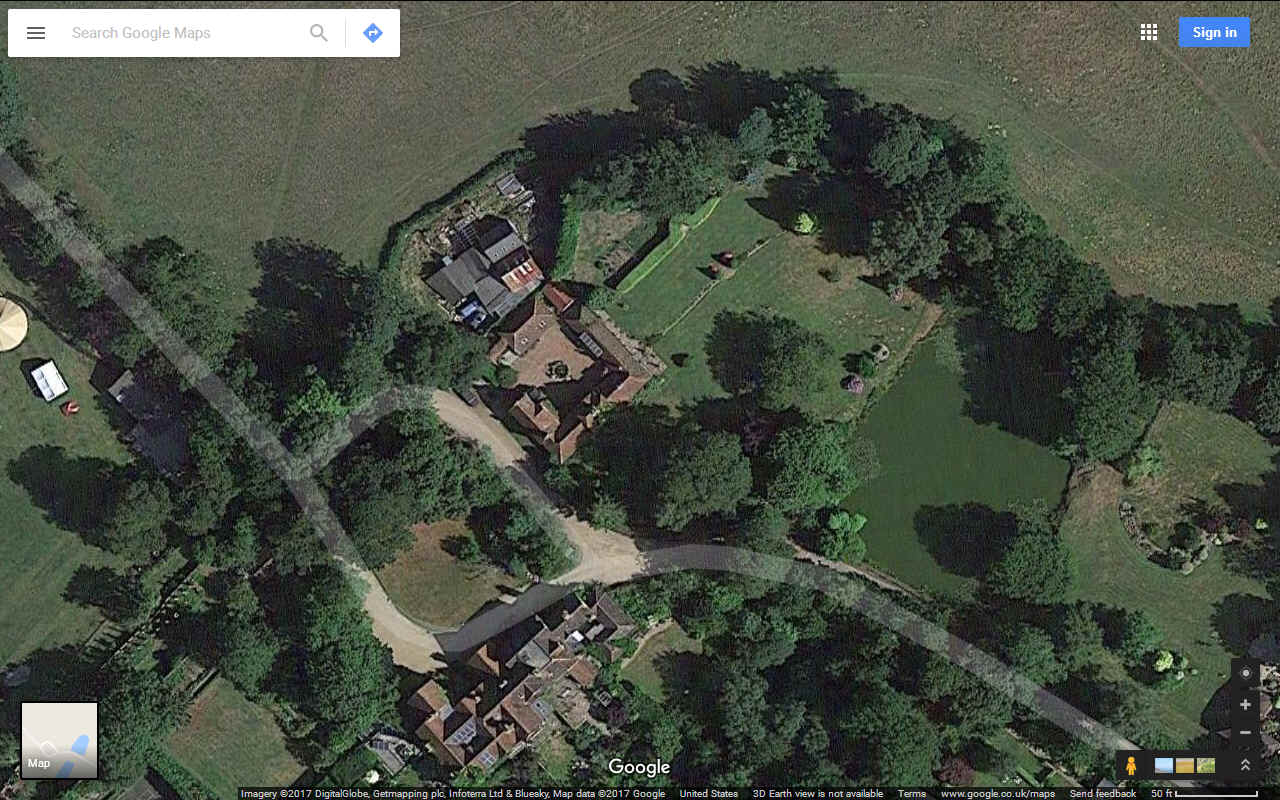

Aerial

view of the old stables complex in Lime Park, ponds and shared drive,

before demolition of the shed in the top right hand corner and extension

of the north corner, east. Screen shot from Google maps. Testament to a

bygone age.

Some carriage makers went on to produce automobiles. One notable example is the Studebaker brothers. They started as blacksmiths and wagon makers in the mid-19th century. Their company,

Studebaker, initially produced horse-drawn wagons and carriages. As the automotive industry emerged, they successfully transitioned to manufacturing automobiles.

The Studebaker Corporation became a significant player in the early automotive industry, producing both electric and

gasoline-powered vehicles. They continued to innovate and adapt, becoming one of the few companies to make a successful transition from horse-drawn vehicles to motorized cars.

BLACKSMITHING

This ancient craft, often overlooked, played a pivotal role in the birth of industry. It’s not just about brawn and brute force; blacksmithing requires skill, precision, and a deep understanding of materials. Imagine the ring of the hammer, the sparks flying, and the raw power transforming iron into tools, weapons, and machinery. That’s blacksmithing.

It’s a testament to human ingenuity and determination. And this legacy of craftsmanship and innovation continues to shape our world today. Blacksmithing’s techniques and innovations paved the way for the evolution of manufacturing, shaping the world as we know it today. With automation, the blacksmith shop saw a resurgence, prompting the creation of a blacksmith association.

Excavation

inside of a 3 meter area in relation to adjacent buildings, and 6 meters

at a 45 degree angle, could

undermine the provisions of the Party Wall Act as may be alleged. This

digger is clearly excavating within the prescribed (safe) distance of

the Generating Station. The County Archaeologist was informed, to record

the event in case of any future subsidence arising. The local authority

had drawn the attention of the owners of the Rectory to the 'Act' in a

previous planning consent, during a planning application made by Peter

Townley, renewed by his daughter Alison

Deshayes, before sale of the stable complex to Jill Finn and Nigel Flood. Note the

asbestos outbuilding, roof covered by steel sheeting, but the asbestos

wall cladding open to the elements. Presumably at some point in the

future needing to be disposed of by suitably qualified personnel.

RAILWAY DEVELOPMENT

The rise of the railway system owes a nod to the crafty work of modern blacksmiths. The blacksmith first forged wrought iron using heat treatment to create durable carriage and fastener parts. This ironworking prowess, championed by the Association of

North

America, enabled them to hold the iron and forge weld essential metal parts, propelling the development of railways.

In the grand scheme of things, the sweat and sparks of the humble forge played a pivotal role in shaping the face of modern manufacturing. Blacksmithing, with its artisan specialty in manipulating

carbon content in small furnaces, laid the groundwork for the birth of an industry. This evolution of manufacturing made the metal more malleable, expanding its use beyond ornamental purposes, thereby revolutionizing industries.

FARRIERS

Farriery, or the shoeing of horses and similar animals, is an ancient craft, believed to have been practised first in the

Roman

Empire.

Farriery is defined in the Farriers (Registration) Act 1975 as ‘any work in connection with the preparation or treatment of the foot of a horse for the immediate reception of a shoe thereon, the fitting by nailing or otherwise of a shoe to the foot or the finishing off of such work to the foot’.

A farrier is a skilled craftsperson with a sound knowledge of both theory and practice of the craft, capable of shoeing all types of equine feet, whether normal or defective, of making shoes to suit all types of work and working conditions, and of devising corrective measures to compensate for faulty limb action. Farriery is hard physical work and is practiced on animals, some of which may be fractious. Shoes may be made from metal and from other modern materials such as

plastics and resins.

Don't confuse 'Farriers' with ‘Blacksmiths’ although they share

similar base skills. A farrier works with horses but needs training in blacksmithing in order to make the shoe properly. A blacksmith is a smith who works with iron and may never have any contact with horses.

A farrier combines some blacksmith's skills (fabricating, adapting, and adjusting metal shoes) with some veterinarian's skills (knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the lower limb) to care for horses' feet. Traditionally an occupation for men, in a number of countries women have now become farriers.

In countries such as the United

Kingdom, people other than registered farriers cannot legally call themselves a farrier or carry out any farriery work (in the UK, this is under the Farriers (Registration) Act 1975). The primary aim of the act is to "prevent and avoid suffering by and cruelty to horses arising from the shoeing of horses by unskilled persons".

However, in other countries, such as the United States, farriery is not regulated, no legal certification exists, and qualifications can vary. In the US, four organizations - the American Farrier's Association (AFA), the Guild of Professional Farriers (GPF), the Brotherhood of Working Farriers, and the Equine Lameness Prevention Organization (ELPO) - maintain voluntary certification programs for farriers. Of these, the AFA's program is the largest, with about 2800 certified

farriers. Additionally, the AFA program has a reciprocity agreement with the Farrier Registration Council and the Worshipful Company of Farriers in the UK.

HERITAGE

TRAGEDY? - Demolition of the stables/forge building roofline in 2022.

The wooden shed with tin roof, clearly visible in the 'Google Maps' satellite

view to the right, having been already demolished.

KEEPING THE SKILLS ALIVE TODAY

Horse-drawn coaches and buggies, like those used in the Wild West or Victorian England, are mostly seen today in Movies and TV Shows, such as historical films and series. Productions like cowboy films and

BBC period dramas often use these vehicles to create authentic historical settings.

Tourism and Leisure: Some historical sites and tourist destinations offer horse-drawn carriage rides as a nostalgic experience.

They are sometimes used for special events, such as weddings or parades, where a touch of historical charm is desired.

Historical Reenactments and Museums: Events that recreate historical periods often feature horse-drawn vehicles.

Many museums display these vehicles as part of their collections, preserving the history and craftsmanship of the era.

Private Collectors and Enthusiasts: Restoration Projects: Some private collectors and enthusiasts restore and maintain these vehicles, keeping the tradition alive. While they are no longer a common mode of transport, the craftsmanship and history of horse-drawn coaches and buggies continue to be appreciated and preserved in various ways.

Demolition

works in 2022, the shed and roof of the former stables, converted to

garaging, and then to residential use. Meaning the loss of two dedicated

garage parking spaces in Lime Park. Though, a new drive was installed to

the south, for parking of cars outside. This may have altered the

character of the old stable block in heritage terms.

TYPES OF HORSE DRAWN VEHICLES

There are many types of horse-drawn vehicles, each designed for specific purposes and styles. Here are some of the most notable ones:

1. Hackney Coach - One of the oldest styles, popular in the 17th century, used privately and for-hire carriages, often licensed and regulated. This was a four-wheeled carriage drawn by two horses, seating for six passengers.

2. Stagecoach - The iconic vehicle of the Wild West was used for public transportation through cities and long-distance travel. The features were enclosed with windows and a roof, seating for six inside, sometimes additional seating on the roof, drawn by four to six horses.

3. Buggy - A light and simple design used for personal transportation. Buggies featured two or four wheels, seating for two, often with a folding top, drawn by one or two horses.

4. Hansom Cab - Designed for speed and safety and used for vehicle hire, replaced the hackney carriage.

Featuring a two-wheeled, light design, seating for two, driver sits behind the vehicle, drawn by one horse.

5. Landau - Luxury carriage used and favored by aristocrats for showing off clothing. This was a four-wheeled vehicle with a roof that can be pulled down. Seating was for four to six, coachmen sit in an elevated seat.

6. Phaeton - An open carriage used for leisure rides. Featuring a four-wheeled, light and sporty design, often with a high seat for the driver.

7. Barouche - An elegant and luxurious carriage used for formal occasions. Featuring a four-wheeled, open design with a folding top, seating for four, often used for ceremonial purposes.

8. Post-Chaise - Used for fast and long distance travel. Featuring four-wheels, enclosed, seating for two to four, drawn by two or more horses.

These vehicles, while no longer common for everyday transport, are still appreciated for their historical significance and craftsmanship. They are often seen in movies, historical reenactments, and special events.

JULY

2022 - The original roofing line was extended unsympathetically (in

archaeological terms) over the footprint of the tin (potting) shed, and

past that footprint east by a considerable amount. Way past the block

that identified the origins of the stable courtyard; altering the

character of the equine origins of the complex. Property developers

frequently ignore 'character' in the quest for greater floor area to

assist uplift in property value when selling on. A property developer

need not be a typically commercial enterprise by a limited company or

partnership, but a private owner/occupier, taking advantage of capital

gains tax laws over a number or years, as they move from one conversion

to another, profiting as they go. Alternatively, properties may be

purchased and left in Trust in a Will to offspring to avoid Death

Duties. Not so in this case, according to the Land Registry. But time

will tell. This development took place without planning consent - under

permitted development rights, attracting a retrospective application

some months after construction work was near completed - not necessarily

indicative of the intention to sell. Permitted development rights as per

the 2015 Order, allows householders to extend property by a good

percentage without the need to apply for planning permission. New laws

in 2024 make development outside of such 'Rights' lawful after 10 years

without challenge by an Enforcement Notice. Before January 2024 immunity

from enforcement was acquired after 4 years.

THE MOST FAMOUS HORSE DRAWN CARRIAGES

Horse-drawn carriages feature prominently in many classic works of literature, often symbolizing wealth, status, or pivotal moments in the story. Here are a few notable examples:

1. Jane Austen’s Novels

Mr. Bingley’s Chaise and Four in Pride and Prejudice: This carriage signifies Mr. Bingley’s wealth and social status when he arrives at

Netherfield. Anne Wentworth’s Landaulette in Persuasion: A stylish and elegant carriage that reflects Anne’s refined

taste.

2. Charles

Dickens’ Works

The Coach in A Tale of Two Cities: The mail coach that carries Mr. Lorry to Dover is a symbol of the journey and transformation central to the novel’s plot. Mr. Pickwick’s Carriage in The Pickwick Papers: This vehicle is often used for comic effect, reflecting the whimsical adventures of Mr. Pickwick and his friends.

3. Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women

Laurie’s Sleigh: In this novel, Laurie uses a sleigh to take Jo and her sisters on a memorable winter outing, highlighting the close relationships and joyous moments shared by the characters.

4. Anna Sewell’s Black Beauty

The Cab: Black Beauty’s experiences as a cab horse in London provide a poignant commentary on the treatment of working animals and the social conditions of the time.

5. Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina

Anna’s Carriage: The luxurious carriages used by Anna and other aristocratic characters underscore the opulence and social divide of Russian society in the 19th century.

These carriages not only serve as modes of transportation but also play significant roles in the narratives, reflecting the characters’ social standing, personality, and the historical context of the stories.

EXAMPLE

OF POTENTIAL STATUTORY NUISANCE

- This is an area of land that is open to the public visually, being

visible by the users of a shared drive, where rats have been noted in

the waste bags, and the situation largely unresolved in September 2024,

being a virtual tip, allegedly. Copyright picture © 2022 Herstmonceux

Museum Limited.

A

SHORT HISTORY OF STABLES

The phrase: “A Mongol without a horse is like a bird without wings,”

sums up how entrenched horses were with the Mongolian lifestyle. But even with the deep fascination

and reliance on horses in Mongolia, you’d not find fences or stables; especially in their distant past.

We need to go to Ancient

Egypt to find the first trace of a horse stable. The world’s oldest stables were discovered in 1999 in the ancient city of Qantir-Piramesse in

Egypt. It seems that they were established by Ramses II (1304-1237 BC) to breed horses for war, hunting and recreation. These stables are the largest ever found, covering approximately 182,986 square feet and housing 480 horses at a time. They consisted of six rows of halls with sloping floors, divided into stalls for the horses, and a vast courtyard that was probably used as an exercise or practice yard.

In Roman times horse stables were a large part of the Roman Empire, and recently in 2014 the stables of the great Emperor Augustus were discovered during a car park excavation in

Rome. The remains of the horse stable are reported to be made from marble, and ancient graffiti boasts of victories in races at the Circus Maximus. Unfortunately, due to lack of funding the discovery

was reburied with waterproof cloth for future generations to discover.

For more recent evidence of horse stables, we need to move forward to the medieval times.

THE MIDDLE AGES

Horses have always been expensive animals, but in the past they were working animals, used for transport, communication, and battle as well as a statement of status. Every farm had its own horse and it was considered as a valuable commodity. This is why stables were complementary to the house, or built as close as possible to it. Furthermore, their quality had to be better than other farm buildings, as keeping their horse in prime condition was vital to the economy of the household.

During the Middle Ages, in the period between the 5th and 15th centuries, castles had the primary function of being used for defense. Every architectural element was designed to ensure this function, without putting particular attention to their appearance. In the same way, medieval stables were merely functional and had no trace of aesthetic value. They often included hay-lofts and room for the grooms or stables hands to sleep. It is believed that medieval stables were rare because horses were probably left outside during summer and hosted in stables only in the winter.

In 2013 a team of archaeologists from Czechoslovakia,

Australia and the

United

States, explored the remains of a medieval stable located near a castle in the South-East of the Czech Republic. This discovery represented a unique opportunity to study the architecture of the stable, its maintenance and horse care. It is a precious testament

to how a real medieval horse stable worked and functioned.

The archaeologists found three main purposes for the stable. It was used as a temporary accommodation of courier horses, horses bred for battle or simply horses belonging to the people who worked in the castle.

According to the experts, it seems that the stable was constructed in two phases. It is also thought that it was

(originally) larger than the actual size of 14 metres by 2.5 metres, with the entrance being 1.6 metres wide. The roof was supported by crossbeams made of timber, every two metres along the walls, and the thickness of its infill was 80 centimetres. The stables might have been totally rebuilt during the second phase of the construction, with the exception of its foundations. This new building was divided by two walls which created three rooms and could host up to seven horses. The researchers believe that two of the new rooms served for the accommodation of pregnant mares or superior horses and their preparation. The rooms both had

wooden floors.

THE GOLDEN AGE OF STABLES

Free-standing stables started being built from the 16th century onward, and from the 17th century they were designed to complement the architecture of the houses. Elements such as clock towers, entrance arches, large yards and different materials (like stucco, wood, bricks and stone) became indispensable features. The stables were designed to take account of local building materials, popular architectural styles

and the weather.

It became quite popular to build stables which looked like houses, with symmetrical windows and large doors, as well as the idea of giving horses their own space. What we call

a ‘stall,’ started being planned specifically to cater for sick horses or foaling mares.

During the Georgian era (1714–1830) stables were built with stones or bricks, often within a courtyard. To provide access to the horse accommodation and other rooms, there was a passage from the stable yard, but sometimes harness rooms were located in other buildings. The fodder was stored in a hayloft above the stables and living quarters were often created for the grooms or other stable staff. The horses were accommodated in stalls and tied with a

rope, with a stone or wooden weight on its end.

As for loose boxes, they were not so popular due to the large space needed for them. In case of necessity, boxes were used to keep stallions or foaling mares. Within the courtyard there were feed rooms, storerooms and a coach-house. Surviving seventeenth century stables can also be seen at Dunster Castle, Somerset.

The Victorians (1837–1901) improved the lives of their horses by giving them extra comfort and hygiene, and by building more solid and robust stables, with draught free ventilation and damp free floors through drainage channels. They drew up rules on how horse stables should be built to specific specifications.

From the second half of the 19th century stables were built not only for housing horses, but also for showcasing the owners’ power, wealth and pride. Horses offered transportation and they often were the most valuable asset of an estate. Stables were a true luxury and a huge amount of money was spent to buy the finest horses, bred to ride and pull carriages. Livery men were often among the best paid domestic staff, and the

richest people traveled the world in search of the most beautiful breed of horses. Famous architects were asked to design not only functional, but beautiful structures with rooms for offices, bridles, saddles, blankets and carriages.

MODERN STABLES

Soon, progress was galloping faster than horses and by the 1860s people began riding bicycles, flying airships and reading about steamships in the newspaper. Technology was moving at an ever increasing pace and towards the end of the

Victorian period, motor cars were being developed. Horseless carriages, like cars, vans and motor cycles were to spell the end of our reliance on horses once and for all, and though accessible only to the wealthiest in the beginning, these new inventions were soon to be used by everyone.

After WWI, many stable buildings fell into disrepair. They were no longer a necessity, and were expensive to the point of being a pure luxury. Also because maintenance costs were so high it was actually cheaper to buy one of the new fangled machines that ran on

petrol or diesel

internal combustion

engines.

People gave up horses and converted old stables into domestic homes, offices, restaurants, museums, workshops, offices, pubs and shops.

This market

actually had working stables for workhorses. The last horse was moved out in 1967. At that time there was a horse hospital, a blacksmith shop and horse stalls here. There are boards with the market’s history on many walls. You can still see the beautiful bricked arches and lovely cobblestone floors. More than 400 horses used to be housed here to transport the canal building materials for the Regent’s Canal and for the construction of the railway network. You can see interesting horse statues above the arches of the shop.

CAMDEN

STABLE MARKET

One of the most famous examples is part of Camden Market, in London. It is the Stable Market and was a large stable building, built in 1854 to look after horses. The entire area was a hive of activity in the last part of the 19th century, because goods were loaded on and off canal boats and distributed by horse and cart across London.

Part of the famous cluster of markets known collectively as Camden Market, The Stable Market is located in the historic former Pickfords stables and Grade II Listed horse hospital which served the horses pulling Pickford's distribution vans and barges along the canal. Many of the stalls and shops are set in large arches in railway viaducts.

The Stables Market was owned by Bebo Kobo, Richard Caring and Elliot Bernerd of Chelsfield Partners until 2014. It was sold in 2014 for $685 million to Market Tech PLC, a UK AIM listed public company, later named LabTech. The market is located in the historic former Pickfords stables and Grade II

listed horse hospital which served the horses pulling Pickford's distribution vans and barges along the canal. Many of the stalls and shops are set in large arches in railway viaducts.

Chain stores are not permitted and trade is provided by a mixture of small enclosed and outdoor shops and stalls, of which some are permanent, and others hired by the day. In common with most of the other Camden markets the Stables Market has many clothes stalls. It is also the main focus for furniture in the markets. Household goods, decorative, ethnically-influenced items, and second-hand items or 20th-century antiques, many of them hand-crafted, are among the wares.

After being heavily bombarded during World War

One, the stables were then restored and today make up one of the most famous attractions in London.

Vast

roof extension to the east in July of 2022. At least capturing carbon,

in the quantity of timber used. The developer fell out with this

builder, after internal works did not work as anticipated. Damp has

always been a problem, as the retaining wall abutting the Museum, may

have been tanked when first constructed, but bitumen and render tanking

invariably breaks down over the years. Requiring remedial works as the

years take their toll. In the case of the retaining wall, it was

remedially tanked on the inside of the former stable building.

CHAPTERS

|

The Industrial

Revolution

|

|

|

Electricity and Magnetism

- Electric

Lighting Acts 1882 - 1909

|

|

|

Let there be light,

glass bulbs to LEDs

|

|

|

Public supply

|

|

|

Rural supply

|

|

|

Lime Park

|

|

|

Generating station 1982/3

|

|

|

Generating station – Power House,

36 hp National Gas engine

|

|

|

Honeysett

Brothers - Electric Bakers & Confectioners, Gardner Street

|

|

|

Flour

from the millers at Windmill Hill (Trust), tallest post

windmill, UK

|

|

|

Archaeology – Machinery

|

|

|

Archaeology – Boiler Room

|

|

|

Archaeology – Batteries

|

|

|

Sussex Express & Kent Mail Oct 1913

- cooking demonstrations

|

|

|

Coal deliveries &

plan of building

|

|

|

Map of Herstmonceux

|

|

|

Stabling,

horses, carriages & blacksmiths - The Old Rectory

- conversion

|

|

|

The Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society

|

|

|

The County Archaeologist

|

|

|

The chauffeur’s daughter

|

|

|

The engineer’s son

|

|

|

The Department for Culture Media & Sport

(DCMS)

|

|

|

English Heritage & Monument

At Risk Protection Programmes MARS

|

|

|

Sussex Express

December 1999

|

|

|

Archaeology South

East, London University, Survey & Report 1999

|

|

|

Generating Works -

Instructions 1911

|

|

|

Amberley

Museum, Arundel, West Sussex

|

|

|

The rise of

renewables & climate cooling

|

|

|

UNESCO World Heritage Convention

|

|

|

Site

Restoration and Development Proposals - Phases - 3D

VR

|

ONE -

TWO -

THREE -

FOUR - FIVE |

ANTHONY

SADDLES UP - Anthony is seen here with his shiny new saddle and

stirrups. He wants anther ladder on his left, so that people riding him

can mount and dismount more easily. Saddles that are developed for

horses may not fit other animals, such as camels. This saddle was

originally designed for ponies.

Visitors

to the Museum wanting to ride Anthony, do so at their own risk and will

need to sign a disclaimer. In the Antman

film 2015, Paul Rudd does not use saddles on the ants he rides in

CGI. Without doubt, a properly fitted saddle makes for a more

comfortable ride. At one point in history, stirrups were considered to

be a military secret. Native American Indians did not use saddles when

riding, before European influences. They used bridles and reins, and

mostly rode bareback.

If

you know of any information that may help us complete this story, or if

any of the facts above are inaccurate to your knowledge, please get in

touch and we'll publish corrections once we have verified new

information, credits applied as may be required. It is the nature of

investigating historical issues, that mistakes are sometimes made from

incorrect hypothesizing, while attempting to fill in the archaeological

DNA. Hence, any new evidence will be most gratefully received.

|