|

Thousands of

years ago man knew about electricity, but not enough to do anything

positive with the curiosity. It would not be until electricity could be

applied to lighting, that it would become commercially important, and

traded, just as oil lamps made whalers rich from whale-oil, consigning

candles to the emergency cupboard. Gas lamps too would be displaced,

where electric lighting was safer and brighter. Then came Light Emitting

Diodes (LEDs), solar panels and wind turbines. Early

lead-acid batteries were serviceable, the reason why Shed Three had an

internal drain built in, to allow washing down the floor to remove any

spilt sulfuric acid. We are now in the disposable age, where mend and

make do is a thing of the past.

Between

April and May 1998, the General Secretary of the Sussex Industrial

Archaeology Society (SIAS), Ron Martin, a charity operating in the

Brighton area, took the trouble to visit the electricity generating

station, keen to discover if there were archaeological remains of any

interest, as being claimed. At that time the SIAS were advising on the restoration of the

post windmill, at Windmill

Hill. Thus, Mr Martin did not have to make a

special trip.

A

planning application had been made, for a change of use, to give

equitable reason to spend considerable sums of money on restorations, by

way of a beneficial use. Previously, applications for residential or

commercial uses had been refused, even leading to an Enforcement Notice

in 1987, prohibiting residential occupation. That Notice being based on

information provided to the Secretary of State, by the local authority.

Which as it turns out was poorly founded, and may have been steered more

by

financial considerations, rather than being conservation led. It became

apparent that Councils, don't always follow the correct procedures, for

many reasons, that are discussed in closed session, preventing the

public from knowing how decisions are reached. That may not seem fair to

you, as a member of the public, but that is how the system works.

Another

planning application followed an earlier one introducing the evidence of

Ronald Saunders from June 1997, where there was no

professional archaeological evidence to warrant fresh consideration, the

local authority simply refused the application, saying there were no new

material considerations. Then, almost by magic, there was a letter of

support from the SIAS, al thanks to the sterling efforts of Mr Martin,

meaning, there was now professional evidence on the table. A second

application like this is in effect a free go, as they say, where there would be no additional fee.

This new evidence flummoxed the local authority, rather embarrassing

their planning department heads, as you may imagine. So, caught between

a rock and a hard place, they simply buried their heads in the sand, and

refused to determine the application. About which the Planning

Inspectorate, on behalf of the Secretary of State, advised that if they

had been provided with incorrect information in 1986, and were now

refusing to see reason, that there was no recourse to justice in law

that they knew of, other than a Judicial Review, though potentially

massively out of time and woefully risky.

As

many people may know, a Judicial Review is a very costly affair,

somewhere in the region of £50,000 pounds, and it's still a massive

gamble, because a Single Judge has to be convinced of the merits of the

case, or he or she will not give permission to proceed, that permission

being called: "Leave." Sounds incredible, but that is the

present process. And if you were to be granted 'Leave' you might still

lose the case, where most courts lean in the direction of protecting the

system, as they call it: Noble Cause Corruption. In which case you'd end up

with a massive legal bill, and be staring bankruptcy in the face. There

is no Legal Aid for planning cases. Queen Victoria's promise of giving

law to the people, was dashed on the rocks, of a mounting National debt crisis.

That is far worse now, than in 1998. But even so, the government had

slashed funding to refuse ordinary folk, access to the courts.

But

now, the heat was being turned up in the archaeological cooking pot. Awakening

the interest of the County Archaeologist at East Sussex County Council.

A fine institution headquarter in Lewes, where you may be dismayed to

learn, they actually burned people at the stake just off the High Street

between 1555-1557: The Lewes Martyrs.***

Not

in any way to

make up for the deaths of those poor souls, the County wished to define what archaeological remains were

and should be considered, they

commissioned an independent survey, to be conducted by London

University's Archaeology South East division. The County Council should

have been involved earlier, as is seen in Planning Policy Guidance Notes

(PPGs) 15 and 16. But, the applicant was not advised of this by the

local authority. In our view a rather somber breakdown in performance. However, the

archaeologists that subsequently became involved, including English

Heritage [now Historic England], were keen to

point to this procedural anomaly, though not consider the ramifications

to posterity.

All

attention was thus focused on what the experts would say in their Report

....

A

hive of local activity, in the Sussex backwater of Herstmonceux. The

driver from all of this was electric lighting, to replace candles and

gas lighting.

This

was set to be a battle royal, between the academic world of archaeology,

and the local planning authority, with the then occupiers of the

building trapped in the crossfire - very much unable, or unwilling to

intervene, and unaware of the World Heritage

Convention, that drives

nations to catalogue and protect monuments in their administrative

regions. But certainly unable to afford to mount any kind of informed

challenge, to do the Generating Works justice, correct the defective

record and secure a workable compromise for the future. From past

performance of the combatants, that would require very deep pockets

indeed, and years of negotiations, that have in the past been secured as

Consented Court Orders, and then not acted on.

We

hasten to add, this was not the present Trust, or operators of the

Museum, who thankfully, were not involved in that scrum. The Trust is

though faced with a dilemma. How best to treat the

site, and all those

with an interest, and then finally, how far would restoration need to

go, to attain World Heritage status. As you can read below, the Survey

and Report from 1999, was the result of just three and a half hours of

investigation. Even so, a great deal of useful information is added to

the observations of the SIAS, and Ron Martin, and Ronald Saunders, from

July 1997. With more details added by dear Margaret Pollard, who we

always think of as Peggy Green, growing up in Herstmonceux, in a

different age, and how lucky she was.

ARCHAEOLOGY SOUTH-EAST, INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON

Site The Old Steam House, Lime Park, Herstmonceux, East Sussex NGR TQ 6365 1223

Project Ref 1146 Date of Survey 29/9/99 This revision 30/9/99

THE OLD STEAM HOUSE,

LIME PARK, HERSTMONCEUX, EAST SUSSEX

(Centred at TQ 6365 1223)

COMMISSIONED BY

EAST SUSSEX COUNTY COUNCIL

Project REF. 1146

by

by David Martin FSA IHBC MIFA

&

Barbara Martin AIFA

INTRODUCTION

The report which follows was commissioned by Andrew Woodcock, County Archaeologist for East Sussex. The brief was to carry out a rapid inspection of The Old Steam House, Lime Park, Herstmonceux, with the aim of ascertaining as far as possible how much of the original fabric of the two-gabled part of the building survives, and to identify clues as to its original form. The survey excluded any evidence for plant, unless forming part of the standing elements of the structure.

The inspection was carried out by David and Barbara Martin, Historic Buildings Officers with Archaeology South-East, University College London, on Wednesday 29th September 1999 and was limited to three-and-a-half hours on site.

LOCATION

The Old Steam House is centred at grid reference TQ 635 1223, approximately 150 metres to the north of the house known as Lime Park. And immediately to the north-west of a dwelling now called ‘The Old Rectory’. It comprises a complex of attached single-storeyed tin clad structures, part aligned with its roof ridges running NE-SE (for convenience hereafter assumed to be N-S) and part aligned with its roof ridge running SE-NW (for convenience hereafter assumed to be E-W) – other sections have gently sloping mono-pitched roofs. That part of the complex which forms the subject of this present report forms the northern element of the building as it currently stands and consists of a single block covered by two adjoining parallel roofs, both with their ridges running north-south (figure 2). Formerly, there was a further range attached to the north of the complex, but only the foundations of this now survive.

THE LIMITATIONS OF THIS REPORT

Interpretation of the structure was based upon a visual inspection and (apart from removing two small areas of loose coverings) included no intrusive techniques. Externally the majority of the walls and all the roofs are clad in corrugated tin, whilst internally below roof level most of the constructional details of the walls are today masked by modern sheet claddings. Only within a small area of the north wall is a section of framing

- 1 -

ARCHAEOLOGY SOUTH-EAST, INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON

Site The Old Steam House, Lime Park, Herstmonceux, East Sussex NGR TQ 6365 1223

Project Ref 1146 Date of Survey 29/9/99 This revision 30/9/99

Visible. With the exception of the roof trusses and purlins, most of the constructional detail within the attic areas is masked by original boarding. Only within the southern gable of the western roof and small areas where boarding within the roof slopes is missing is any constructional detail visible. These factors greatly hindered assessment of the extent of the original fabric and interpretation of the structures sequence of development and original form. These restraints should be borne in mind when considering the findings presented below.

CARTOGRAPHIC AND DOCUMENTARY EVIDENCE

The building is not shown on the 1899 25” O.S. plan surveyed in 1872/3 and fully revised in 1898 (O.S. Sussex Sheet 56/11 – 2nd Edition). A building is indicated upon the site by 1909 (Ibid 3rd Edition) but this scale only c.8.00 metres east-west x c4.00 metres north-south (excluding a small southward projection at the eastern end): the core section of the surviving building measures 11.75 metres x 6.25 metres. In addition to this size variation, the building depicted on the 1909 O.S. plan is shown with a much larger gap than now between it and the adjacent Old rectory, whilst its rear (northern) wall is shown further south than that of the present building. Even allowing for inaccurate surveying, the number of variations between the 1909 depiction and the present building make it all but certain that the 1909 representation is of a building which pre-dated the present structure.

No later editions of the relevant 25” O.S. plan (showing revisions of between 1910 and 1940) were readily available at the time this report was written, and thus it is not currently known when the present building was first depicted on the 25” O.S. plans. However, a report in the Sussex Express for October 10th 1913 states:-

“Few villages of the size of Herstmonceux can boast of being so up to date as to have electricity installed, not only in the streets, but also in the private houses. This was made possible by the enterprise of Mr C W von Roemer [the owner of Lime Park], who by his electric plant supplies electricity by motor.

During the week demonstrations in cooking by electricity have been given… and Mr von Roemer has generously offered to fit an electric stove in any house in the parish free, and to make a charge of 11/2d [per] unit for the use of the electricity. Many people in the village have already accepted the offer, and the results obtained by this new means of cooking are very satisfactory” [Quote supplied by Nelson Kruschandl, via Andrew Woodcock].

There can be no doubt from the physical evidence of the bases and pits for former electricity-generating plant remaining on site, of artefacts relating to electricity generation, and from the signed affidavit of Ronald Saunders whose father worked the plant and who remembers the equipment in situ, that the electricity generating plant referred to in the

- 2 -

ARCHAEOLOGY SOUTH-EAST, INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON

Site The Old Steam House, Lime Park, Herstmonceux, East Sussex NGR TQ 6365 1223

Project Ref 1146 Date of Survey 29/9/99 This revision 30/9/99

1913 newspaper article was located within the building which is the subject of this present report. Although a precise date for the building is not possible based on the typological evidence, the surviving architectural details are entirely consistent with an early-20th-century date. It therefore seems fair to suggest that the building shown on the 1909 25” O.S. plan was purposely rebuilt in or a little before 1913 in order to house the electricity generating plant. As will be noted below, some alterations (currently not entirely understood) were made to thee building subsequently.

ARCHITECTURAL DESCRIPTION

The section of building which forms the subject of this present report is a rectangular structure measuring 11.75 metres (38’6”) east-west and 6.25 metres (20’6”) north-south. It is single storeyed and is covered by two parallel roofs aligned north-south and divided by a central valley. There is today an attic floor supported by joists inserted during the 1990s, though these replaced a loosely-laid earlier attic floor [pers. Comm. Nelson Kruschandl]. The visible structural evidence suggests that this earlier floor was not original and that the building was initially open to its roof. The storey height from floor to underside of the tiebeam is 2.73 metres (9’0”).

As far as can be seen from the visible evidence, this section of the building is entirely of timber stud construction built off a brick ground wall. Horizontal rails are morticed and tenoned (joints pegged) between the studs in order to carry vertical internal and external boarding. The boards, where they survive, are beaded. Most of the studwork and noggings are 104mm x 52mm (4” x 2”) scantling, but incorporated into the walls are heavier studs 104mm x c.225mm (4” x 9”) [only one of these (in the north wall) was visible: Nelson Kruschandl knows others exist}. A small area of structural detail is visible at the north-western corner, and here there is no corner post, but instead a series of heavy horizontal noggings have been roughly sawn through and clearly formerly extended westwards. They still support external boarding identical to that elsewhere in the building. Insufficient is visible to ascertain why the wall detail is varied at this point, but the westward extension is known to have formed part of a now-demolished range which stood to the north. Although it would need to be confirmed by intrusive investigation, it would appear from the available evidence that this northern range of building was of the same date as that section which forms the subject of this report.

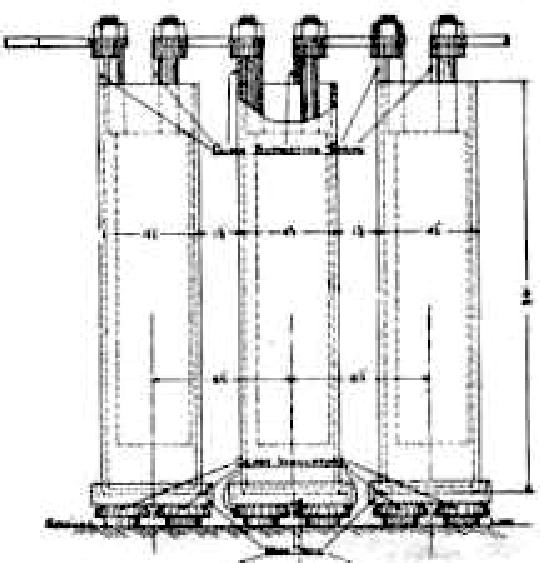

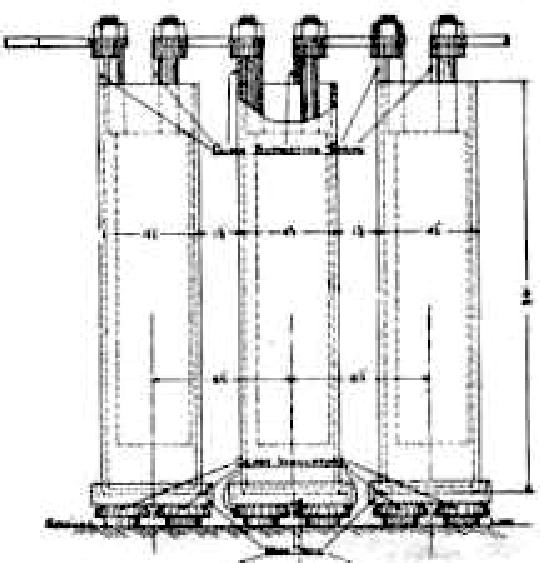

Both sections of roof within that part of the building here under investigation are of similar construction, but with some minor variations in detail (see figure 4 and below). They are framed in three bays and have studwork gables to north and south. They are of textbook kingpost construction with splay-cut jowls at the base of the posts (to support struts) and similar jowls at the head (carrying the inset principal rafters). The principal rafters and purlins are exposed to view, but the common rafters which the purlins carry are hidden from view by beaded under-boarding identical to that used on the walls. Investigation

- 3 -

ARCHAEOLOGY SOUTH-EAST, INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON

Site The Old Steam House, Lime Park, Herstmonceux, East Sussex NGR TQ 6365 1223

Project Ref 1146 Date of Survey 29/9/99 This revision 30/9/99

through small broken areas allow the constructional details to be ascertained. There are no wallplates, but instead the common rafters are carried over the backs of the lower tier of purlins. In addition, there is a central line of purlins. At the head the common rafters meet at a ridgeboard. The common rafters are set at approximately 660mm centres. Located centrally within each slope of each bay within the western roof is an (apparently original) rooflight. These are an identical number of rooflights within the eastern roof, but these are located less symmetrically.

Some original joinery details still survive. The external and internal boarding and the rooflights have already been mentioned. In the northern gable of the western roof is a shuttered hatch. The shutter is top hung, opens inwards and was operated from the ground by a pulley (still extant). In the southern gable of the same roof and within the northern gable of the eastern roof survive original four-pane windows, and there is another original window towards the eastern end of the northern ground-floor wall. Many of the openings retain their moulded architraves, whilst the ground-floor window also retains external architraves.

The ground floors contain evidence in the form of plinths, pits and ducts as to the original form of the power plant, but these are beyond the scope of the present report. In the main, the floor within the western part is of flag stones (interrupted by plant pits etc and at one point made good where a machine base has been removed), whilst the eastern part is of concrete. Between the two is an infilled internal ramp which allowed access to the eastern and western rooms. The eastern concrete floor incorporates a 160-170mm upstand along its eastern and southern sides, together with a drain-down gully in the south-west corner and a raised plinth in the north-east corner. According to Ron Saunder’s signed affidavit, when he knew the building this area was used to house accumulators.

There is some structural evidence to hint that the section of building under investigation is of two phases of construction, though if so the two phases are of very similar date. The evidence, which is found both in the constructional details and in the building’s design, is not conclusive. The variations in constructional details are slight, but may be significant. The joints to the roof trusses within the eastern roof are pegged, though those within the western roof are not, whilst in the western roof the struts meet the principle rafters in line with the central purlins, whereas within the eastern roof they joint into the principle rafters above the central purlins. The design anomalies are more puzzling. Although the two roofs run parallel to one another (being separated by a central valley) they are of different spans and heights – the overall span of the western roof is 5.50 metres (18’0”) compared with 6.25 metres (20’6”) for the eastern roof. If of one period, this would only make sense if there was an internal partition beneath the central valley, but such an interpretation is not supported by the surviving evidence – the widest room was beneath the narrowest pitch and encroached in to the eastern roof pitch. Taken together these two pieces of evidence suggest that the structure was built in two phases and that when the addition was made the internal layout was modified. Unfortunately, because the structural detail is not visible,

- 4 -

ARCHAEOLOGY SOUTH-EAST, INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON

Site The Old Steam House, Lime Park, Herstmonceux, East Sussex NGR TQ 6365 1223

Project Ref 1146 Date of Survey 29/9/99 This revision 30/9/99

The evidence to confirm or deny this hypothesis is not currently available. If the structure is indeed of two phases, then it is the eastern section which is the earlier part, for the two tiebeams which cross the building east-west are each formed from two timbers (one to the eastern roof and one to the western roof). These two sections of timber extend past one another and are joined together by means of three bolts. In both instances the eastern section of tiebeam terminates in line with the valley, whereas the western section projects by some distance into the eastern roof. There are slight traces of stain on the side faces of the eastern tiebeams, a little from the end, possibly indicating the ghost of a removed wall. Given the doubts, for convenience both elements of the section of building under investigation are deemed to have been constructed during phase 1, but the eastern (possibly earlier part) will be referred to as being phase1A and the western (possibly later part) as phase 1B (figure 2).

Interpretation of the internal layout is hampered by the degree to which the structural details are hidden. One alteration causes no problems, having been made during the last five years or so. This involved removing the wall between the western room and central service ramp and replacing it by a new wall some distance to the west, thereby narrowing the western room and widening the central area [pers. comm. Nelson Kruschandl – compare figures 3A and 3B]. The line of the earlier wall is clearly visible as a stain on the tiebeams. If the structure is indeed of two main phases, then even this earlier wall may have dated from phase 1B, replacing a phase 1A running beneath the western end of the eastern tiebeams. There is some slight staining on the side of the phase-1A tiebeams to support this conclusion, but the evidence is far from conclusive.

There is structural evidence to show that there has been modification to the layout within the eastern part of the building. A heavy structural post in the northern wall and located approximately beneath the ridge line of the eastern roof is notched for a heavy (c150mm x c. 310mm) bearer running north-south immediately beneath the tiebeams. Although, now hidden, there is a corresponding post in the south wall [pers. comm. Nelson Kruschandl]. The line of the bearer is shown as a stain on the underside of the southern tiebeam – the soffit of the northern tiebeam is masked by later work. Further, the marks of a light fitting on the southern tiebeam are located centre span between the stain left by the bearer and the eastern wall. As additional proof, the southern upstand on the concrete floor is made good on the line of the removed bearer. Given this evidence, there can be little doubt that the removed bearer formed the headplate of a now lost partition (figure3C). What is clear from the evidence contained within the structural ground floors is that the modified layout as shown in figure 3B belonged to the period when the building was still in use for the generation of electricity.

- 5 -

ARCHAEOLOGY SOUTH-EAST, INSTITUTE OF ARCHAEOLOGY, UNIVERSITY COLLEGE LONDON

Site The Old Steam House, Lime Park, Herstmonceux, East Sussex NGR TQ 6365 1223

Project Ref 1146 Date of Survey 29/9/99 This revision 30/9/99

A BRIEF NOTE ON OTHER PARTS OF THE BUILDING

Attached to the north of the section under investigation, and projecting slightly to the west, was a second attached building or range. This has been demolished, though its foundations and plant bases still survive. From the structural evidence visible at the north-western corner of the surviving building (see above) this demolished range appears to have been contemporary with the surviving phase-1B section. Attached to the south wall of the section under consideration is a further building or range, roofed east-west and apparently representing an addition to the main part made whilst the building was still in use as an electricity generating station. Beyond this to east and south are later ‘flat roofed’ additions (figure 2). At the extreme southern end of the complex is a ‘faggot store’: located upon the site of a building shown on the 1909 25” O.S. plan and may incorporate some external brickwork of that period.

CONCLUSIONS

Despite alterations to the original internal layout, there can be little doubt that much of the original structure still survives. Despite some minor modifications, the roof structure and internal finishings within the roof void remain largely intact. Regarding the external walls, the west wall has been completely rebuilt during the last 10 years, but although elsewhere within the external walls little of the structural evidence is visible, the survival of early external boarding beneath the later corrugated coverings indicate that most of the early structure still remains. To judge from the small area exposed (which shows evidence of a lost partition) this hidden detail will contain much information which would allow the development of the building to be better understood. Likewise, although excluded from the present report, the floors contain much significant surviving evidence.

It will be clear from the contents of this report that, although the building was in use for the generation of

electricity over a relatively short time between 1909x1913 [O.S. plan and newspaper report] c.. 1925 [sworn affidavit says about 1920, but from other evidence probably nearer 1930] the plant appears to have developed and expanded during that period. The generation of electricity lies outside the competence of the present writers, but it is interesting to note that the 1913 newspaper article refers to the generation of electricity ‘by motor’ whereas the sworn affidavit relating to the plant late in its life refers to generation by steam engine. Was the take-up by the local community sufficient to require an initial small-scale operation to be considerably enlarge and improved, thus accounting for the apparent major expansion hinted by the architectural remains?

This present report is limited to an investigation of the standing remains of one part of the surviving complex

and is entirely dependant upon the visible evidence. The significance of the remains which survive lies outside the scope of this document.

- 6 -

FIGURE

1

FIGURE

2

FIGURE

3

FIGURE

4

FIGURE

5

ABOUT

ARCHAEOLOGY SOUTH EAST - INSTITUTE OF FIELD ARCHAEOLOGISTS

CONTACTS

University College London

Gower Street

London WC1E 6BT

United Kingdom

Tel: +44 (0) 20 7679 2000

Email: library@ucl.ac.uk

Email: postmaster@ucl.ac.uk

Archaeology South-East is part of the UCL Institute of Archaeology

General enquiries: ase@ucl.ac.uk

HR enquiries: ase-hr@ucl.ac.uk

Finance enquiries: ase-accounts@ucl.ac.uk

Sussex office

Archaeology South-East, Units 1 & 2, 2 Chapel Place, Portslade, Brighton, East Sussex, BN41 1DR

Telephone: +44 (0)1273 426830

London office

Archaeology South-East, UCL Institute of Archaeology, 31-34 Gordon Square, London, WC1H 0PY

Telephone: +44(0)20 7679 4778

Essex office

Archaeology South-East, 27 Eastways, Eastways Industrial Estate, Witham, Essex, CM8 3YQ

Telephone: +44(0)1376 331470

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology-south-east

https://www.ucl.ac.uk/archaeology-south-east

COMMENT

We don’t think that we need to add anything to the above report at this stage. Anyone reading this survey would know that the Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society was spot on about the original form of most of the buildings, including the timber

structure in May of 1998. That of course means that for the past forty years, the local authority officials having conduct of the case up the this Report, have for some reason been blinkered, proceeding not to discover the facts, but content to pursue a course of conduct that the ordinary man in the street might find more than

a little upsetting. Especially considering the duty imposed on those in

such positions of trust.

We (the Trust) are extremely grateful, firstly to East Sussex County

Council and Dr Andrew

Woodcock, and secondly, to Barbara and David for taking the time to visit the site and for advising and writing to the County Archaeologist on the subject.

CHAPTERS

|

The Industrial

Revolution

|

|

|

Electricity and Magnetism

- Electric

Lighting Acts 1882 - 1909

|

|

|

Let there be light,

glass bulbs to LEDs

|

|

|

Public supply

|

|

|

Rural supply

|

|

|

Lime Park

|

|

|

Generating station 1982/3

|

|

|

Generating station – Power House,

36 hp National Gas engine

|

|

|

Honeysett

Brothers - Electric Bakers & Confectioners, Gardner Street

|

|

|

Flour

from the millers at Windmill Hill (Trust), tallest post

windmill, UK

|

|

|

Archaeology – Machinery

|

|

|

Archaeology – Boiler Room

|

|

|

Archaeology – Batteries

|

|

|

Stabling,

horses, carriages & blacksmiths - The Old Rectory

- conversion

|

|

|

Sussex Express & Kent Mail Oct 1913

- cooking demonstrations

|

|

|

Coal deliveries &

plan of building

|

|

|

Map of Herstmonceux

|

|

|

The Sussex Industrial Archaeology Society

|

|

|

The County Archaeologist

|

|

|

The chauffeur’s daughter

|

|

|

The engineer’s son

|

|

|

The Department for Culture Media & Sport

(DCMS)

|

|

|

English Heritage & Monument

At Risk Protection Programmes MARS

|

|

|

Sussex Express

December 1999

|

|

|

Archaeology South

East, London University, Survey & Report 1999

|

|

|

Generating Works -

Instructions 1911

|

|

|

Amberley

Museum, Arundel, West Sussex

|

|

|

The rise of

renewables & climate cooling

|

|

|

UNESCO World Heritage Convention

|

|

|

Site

Restoration and Development Proposals - Phases - 3D

VR

|

ONE -

TWO -

THREE -

FOUR - FIVE |

If

you know of any information that may help us complete this story, please get in

touch.

***

The Lewes Martyrs were a group of 17 Protestants who were burned at the stake in Lewes, East Sussex, England, between 1555 and 1557. These executions were part of the Marian persecutions of Protestants during the reign of Mary I.

On 6 June 1556, Thomas Harland of Woodmancote, Near Henfield, West Sussex, carpenter, John Oswald (or Oseward) of Woodmancote, Near Henfield, West Sussex, husbandman, Thomas Reed of Ardingly, Sussex, and Thomas Avington (or Euington) of Ardingly, Sussex, turner, were burnt.

Richard Woodman and nine other people were burned together in Lewes on 22 June 1557, on the orders of Edmund Bonner, Bishop of London — the largest single bonfire of people that ever took place in England. The ten of them had not been kept in the town gaol before they were executed but in an undercroft of the Star Inn. The Star Inn became Lewes Town Hall and the undercroft still exists.

Together with the Gunpowder Plot, the Lewes Martyrs are commemorated annually on or around 5 November by the Bonfire Societies of Lewes and surrounding towns and villages, including Lewes

and Battle Bonfires.

Though

now such practices are deemed barbaric, instead they roast you slowly in

the Courts.

|