|

An ecomuseum is a museum focused on the identity of a place, largely based on local participation with the aim of growing the economy whilst enhancing the welfare and development of local communities. It refers in particular to a new idea of holistic interpretation of natural and cultural heritage as opposed to the traditional focus on specific items and objects by conventional

museums.

Ecomuseums originated in France in the 1970’s. There are presently over 300 ecomuseums operating in the world and are prominent in European countries. There is no blueprint for an Ecomuseum, only a shared value of celebrating a sense of place.

Herstmonceux

Museum is an Ecomuseum, not only in the sense of being a community asset, as

an

actual historic building, interwoven in the fabric of the developing

village. But, also, because of the environmental work that has take place in

this location over the years. To wit, the development of electric land vehicles,

and EV refueling systems, and the research into solar and hydrogen powered

ocean transport. Hence, indirectly contributing towards sustainable tourism.

ECO - MUSEIi / ECO-MUSEUM

Eco-museums originated in France, the concept being developed by George Henri Rivière and Hugue de Varine, who coined the term ‘ecomusée’ in 1971. The word “éco” is a shortened form of “écologie”, but it refers mainly to a new idea of the holistic interpretation of cultural heritage, in opposition to the focus on specific items and objects performed by traditional museums. An eco-museum is a museum focused on the identity of a place, based mainly on local participation and aiming to enhance the welfare and development of local communities. There are presently about 300 operating eco-museums globally; about 200 are in Europe, mainly in France, Italy, Spain, and Poland.

Development Introduced by the French museologist Hugues de Varine in 1971, the word eco-museum has often been misused. The definition of an eco-museum is still controversial in contemporary museology. Many museologists sought to define the distinctive features of eco-museums, listing their characteristics. Following a complexity approach, in recent definitions, eco-museums are more appropriately defined by what they do rather than by what they are.

THE ECO-MUSEUM DEFINITION IN CONTEMPORARY MUSEOLOGY

Contemporary museums are more and more museums of ideas rather than museums of objects. In this move, it is harder to establish rigorous definitions. Furthermore, the relative diffusion of the views of the Nouvelle Muséologie only makes the situation more chaotic since many of the characteristics believed to be peculiar to eco-museums, such as in situ interpretation or the involvement of the local community, may actually be typical of and effectively implemented by many of the innovative museums that belong to traditional theme typologies.

From the beginning, one of the most valuable definitions compares an eco-museum with a classic museum: essentially a cultural process identified with a community (population) on a territory, using the common heritage as a resource for development, as opposed to the more classical museum, an institution characterized by a collection, in a building, for a public of visitors (H. de Varine, 1996).

Peter Davis (P. Davis, 1999, Eco-museums: a sense of place, Newcastle, Newcastle Univ. Press) states that the amount of overlap might gauge the degree to which a museum demonstrates essential eco-museum characteristics in a three circles model (community, museum and social, cultural, natural environment) and in its ability to capture a sense of place.

Kazuochi Hoara effectively describes the circles’ contents (K. Hoara, 1998, The image of Eco-museum in Japan, Pacific Friends 25/12).

Maurizio Maggi defines an eco-museum as an exceptional kind of museum based on an agreement by which a local community takes care of a place (M.Maggi, 2002, Ecomusei. Guida europea, Torino-Londra-Venezia, Umberto Allemandi & C.).

WHERE:

– an agreement means a long-term commitment, not necessarily an obligation under the law

– local community means a local authority and a local population collaborating

– take care means that some ethical commitment and a vision for future local development are needed

– place means not just a surface but complex layers of cultural, social and environmental values which define a unique local heritage.

The first three issues are part of the so-called local network, while the fourth is quite close to a milieu. These two elements play a central role in Ire’s present studies on the so-called “Place-based Local System”.

THE CHINESE SCHOOL CONTRIBUTION

Su Donghai (Su Donghai, 2006, Communication and Exploration, SCM-IRES-PAT, Trento- Beijing) summarized the intense work developed by the Chinese and Norwegian museologists (among them, the late John Aage Gjestrum) in the last decade of the 20th century in the Liuzhi Principles.

1. The people of the villages are the actual owners of their culture. Therefore, they have the right to interpret and validate it themselves.

2. The meaning of culture and its values can be defined only by human perception and interpretation based on knowledge. Therefore, cultural competence must be enhanced.

3. Public participation is essential to the eco-museums. Culture is a common and democratic asset and must be democratically managed.

4. When there is a conflict between tourism and the preservation of culture, the latter must be given priority. The genuine heritage should not be sold out, but producing quality souvenirs based on traditional crafts should be encouraged.

5. Long-term and holistic planning are of utmost importance. Short-term economic profits that destroy culture in the long term must be avoided.

6. Cultural heritage protection must be integrated into a total environmental approach. Traditional techniques and materials are essential in this respect.

7. Visitors have a moral obligation to behave respectfully. Therefore, they must be given a code of conduct.

8. There is no bible for eco-museums. They will all be different according to the specific culture and situation of the society they present.

9. Social development is a prerequisite for establishing eco-museums in living societies. The well-being of the inhabitants must be enhanced in a way that does not compromise their traditional values.

DEVELOPMENT

In the 1960s and ‘70s, a new kind of museum, known as ecomuseums, emerged throughout Europe, predominately in France. Based on belief that museums and communities should be related to the whole of life, ecomuseums focused on integrating the family home with other aspects of a community. Similar beliefs during this period helped generate neighborhood museums in the United States and Mexico. Examples include the Anacostia Community Museum in Washington, D.C., and the Casa del Museo in suburban Mexico City which served as the prototype for hundreds of ‘museos comunitarios’ throughout Mexico.

Although organized independently of each other, many of these museums were influenced by the philosophy of Georges Henri Rivière (1897–1985), the French museologist who felt museums should reflect the natural heritage as well as the local culture and distinctiveness of place.

Often created in response to external forces that held the potential for bringing radical change to an area, such as gentrification, an ecomuseum's overarching purpose was to develop a strong sense of common identity. Thus ecomuseums established a new role for museums as mediator in the process of cultural transition and the development of communities.

In 1971, during the 9th triennial Conference of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) held in Grenoble, France under the theme: The museum in the service of man: today and tomorrow, Hugues de Varine, then Secretary General of ICOM, part of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), coined the name “ecomuseums” (“ecomusée” in French). By adding "eco," meaning "home" in Greek, de Varine’s term eco-museum reflected the emerging concept of a “home-museum” or a “territory-museum.”

In 1985, the entire issue of Museum International Quarterly, the UNESCO periodical, was devoted to the ecomuseum concept. Titled “Images of the Ecomuseum,” the journal opened with Georges Henri Rivière’s article, “Evolutive definition of the ecomuseum,” followed by Hugues de Varine’s editorial, “The word Ecomuseum and beyond."

Hugues de Varine compared museums and ecomuseums in the following equations:

Museum = building + collections + visitors and Ecomuseums = territory + heritage + community.

This means that the three essential dimensions of a museum are radically transformed so that

- the museum building is enlarged to include the whole area where the community lives,

- the ecomuseum collections include all of the cultural heritage found in the area, and

- visitors are replaced by community members who become actors in the ecomuseum’s development.

Thus, ecomuseums differ from mainstream museums in significant ways:

First by creating a new sense of place. An ecomuseum consists of a specific geographic area, either rural or urban. It is not just a building that displays valued items even though communities often have a facility or defined space that serves as an information and activities center. For example, the Écomusée du fier monde in Montreal’s Centre-Sud has converted a large former public bath to hold its exhibitions and other cultural or community activities and to house ecomuseum offices.

The second way ecomuseums differed from traditional museums is in the role of the people who live in the area and share a common culture. Residents define the community’s collections, not outside experts, and take responsibility for their care.

Collections include intangible heritage such as traditional lifestyles, local skills and oral history, shared experiences and values, as well as tangible heritage such as important sites and buildings and archival materials. Usually collections are not gathered together inside a museum building but held in situ. Community members learn the proper ways of taking care of objects and ways for developing schematic exhibitions and activities through various workshops and internship opportunities.

The ecomuseum concept was promoted in North America through the efforts of René Rivard, a Canadian museologist, and Pierre Mayrand, a professor at the University of Quebec in Montreal who helped the people of 12 villages located in a remote area of south-eastern Quebec to create the Haute-Beauce Ecomuseum.

In 1984, in Haute-Beauce (Beauce, Quebec), Rivard and Mayrand hosted the first international gathering of ecomuseologists. More than fifty ecomuseum curators and field-staff from France, Germany, Mexico, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United States participated in the conference. The meeting resulted in the founding of the International Movement for New Museology or MINOM (Movement International pour une NOuvelle Museologie). (See also New Museology. In subsequent years these gatherings were repeated in France, Norway, Portugal and Spain.

In 1991, following a five-year educational program guided by the Smithsonian Institution’s Center for Museum Studies, along with René Rivard, Shayne del Cohen and other consultants, the first ecomuseum in the United States opened at the Ak-Chin Indian Community in Maricopa, Arizona. Called Him Dak (translated from O’odham as ‘Our Way’), the museum became a community education center that prompted the study of Ak-Chin prehistoric presence in the Sonora Desert and of their endeavors to develop in this arid environment.

The ecomuseum phenomenon has grown dramatically over the years, with no one ecomuseum model but rather an entire philosophy that has been adapted and molded for use in a variety of situations. Many museologists have sought to define the distinctive features of ecomuseums, listing their characteristics. As many more ecomuseums are established across the world the idea has been growing and the changes in the approach towards the philosophy are reflected in the reactions of the communities involved. In recent time particular significance is the rise in ecomuseology in India, China, Taiwan, Japan, Thailand, Vietnam and Cambodia, with significant increase in Italy, Poland, the Czech Republic and Turkey.

Ecomuseums are an important medium through which a community can take control of its heritage and enable new approaches to make meaning out of conserving its local distinctiveness.

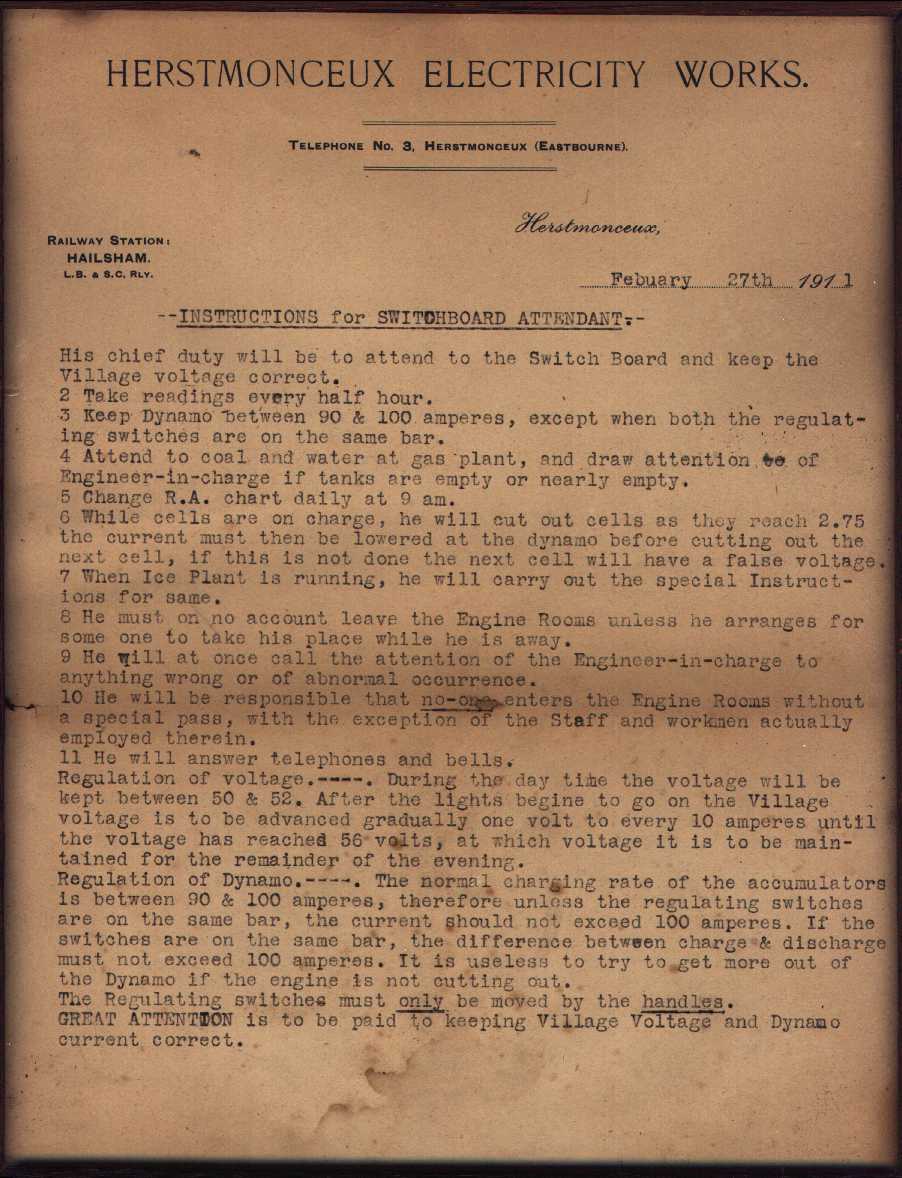

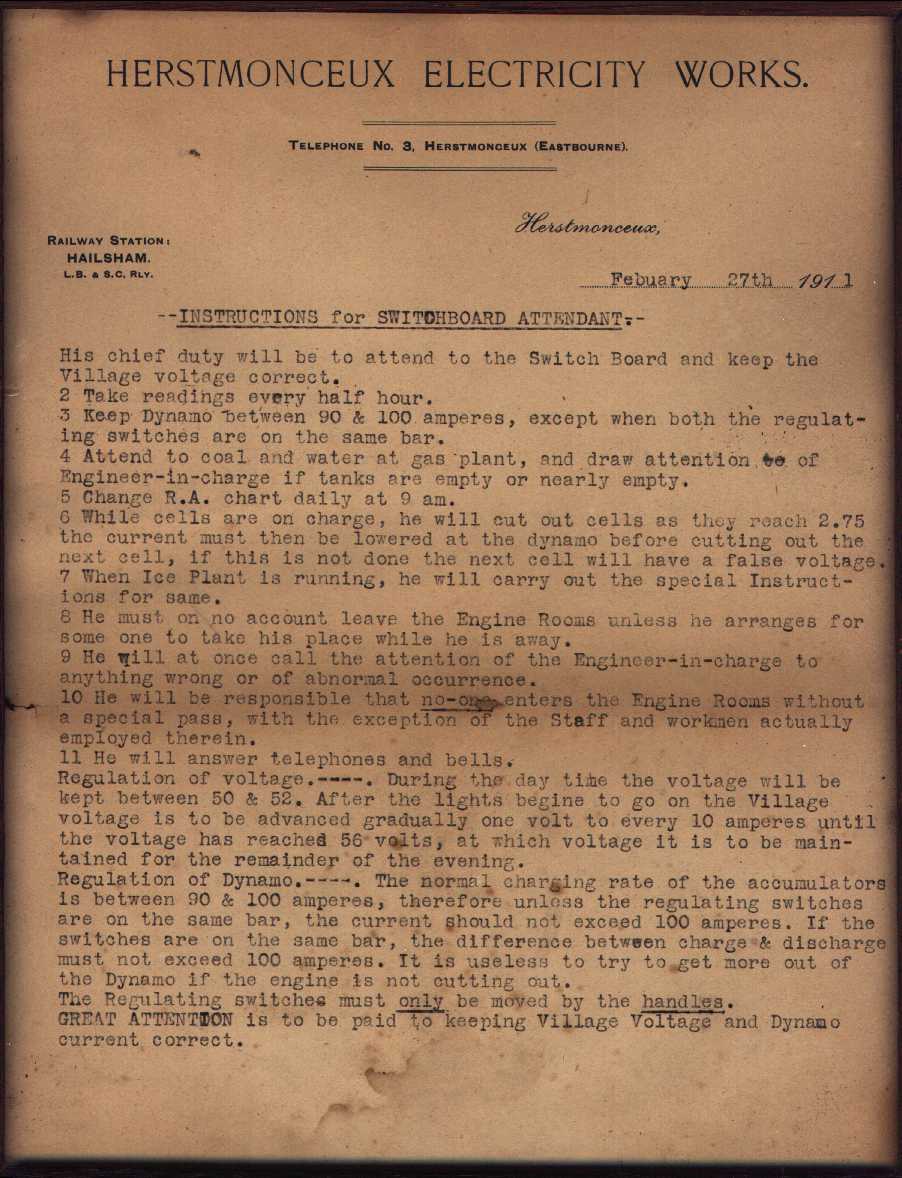

These

instruction from February of 1911, reveal a great deal about the

technology on site. They are one of the exhibits on display, alongside

other innovative firsts that took place in this Sussex backwater.

THE 2016 MILAN COOPERATION CHARTER

In 2016 inside the 24th ICOM General Conference "Museums and cultural landscape" of Milan, the first Forum of ecomuseums and community museums took place. The goals of the forum were to share experiences, questions and difficulties that ecomuseums face; to share their future projects; to envisage any prospect of exchange or collaboration with the visitors. During the Forum "it was proposed to establish an International Platform for exchanges and experience sharing", and "decided to create a permanent international Working Group to keep watch and make proposals on the theme territory-heritage-landscape." In the early 2017 on the basis of ideas, issues and debates raised by participants during the Forum a common vision was drawn and a provisional “Milan Cooperation Charter” was adopted.

THE DROPS PLATFORM

In the early 2017 the world platform for exchange and experience sharing between ecomuseums and community museums was published. The platform called DROPS aims at “connecting all national Ecomuseums and Community Museums and their networks, existing or to be established, and all other heritage and landscape NGOs, in a virtual and interactive space” and at the “production of a multilingual documentary and a bibliographic pool of resources on ecomuseology and its best practices”.

COMMUNITIES & CLIMATE CHANGE - SIGNIFICANT ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS:

Rising global temperatures leading to increased risk of flooding, fire, and sea level rise, resulting in the destruction of property and social infrastructure, loss of biodiversity and tangible and intangible cultural heritage, and damage to economies. Little wonder then that the online conference held on 30 September 2021 with the title “Ecomuseums and Climate Action” attracted more than one hundred participants from countries whose communities are facing these problems.

The 2021 conference is where heritage experts, community activists, curators, politicians and academics from several countries, explored how ecomuseums and community museums are acting as catalysts for transition, renewal, and sustainable development and how they might effectively contribute to the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals and climate action.

How can these organisations best contribute to the debate about the climate crisis and promote local action? Central to those actions are encouraging local people to recognise how important their cultural, natural and intangible cultural heritage is in making places special and giving a sense of belonging, why that heritage should be sustained, and how heritage assets can be used to promote climate action. This book – with its remarkable collection of essays from around the world – demonstrates how small local actions, considered together, can have a dramatic and far-reaching impact. It will be warmly welcomed by anyone interested in climate action, heritage and museum studies, and environmental issues.

INTERNATIONAL COMMITTEE FOR MUSEUMS & COLLECTIONS OF MODERN ART - CIMAM

The International Committee for Museums and Collections of Modern Art – is an Affiliated Organization of ICOM. Founded in 1962, CIMAM’s vision is a world where the contribution of museums, collections, and archives of modern and contemporary art to the cultural, social, and economic well-being of society is recognized and respected.

In January 2022, CIMAM initiated the research project “Climate, Social, and Economic Sustainability: How Modern and Contemporary Art Museums Act to Achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.” The project aimed to assess the commitment of these museums to the United Nations 2030 Agenda’s Sustainable Development Goals.

The study involved professionals from the global modern and contemporary art museum sector, including museum directors, independent curators, heads of exhibitions, trustees, presidents, founders, senior staff, communication experts, sustainability officers, researchers, and educators. Their contributions unveiled the diverse socio-political contexts in which museums operate and the subsequent impact on their ability to develop sustainability plans aligned with the ambitions of the UN Agenda 2030.

Three sustainability experts were invited to evaluate the findings. Caitlin Southwick, founder and CEO of Ki Culture, analyzed the social aspects of the survey. Henry McGhie, founder of Curating Tomorrow, assessed progress towards environmental goals. Martin Müller, professor at the Department of Geography and Sustainability at the University of Lausanne, provided critical insights on the museums’ evolution towards greener economies.

The survey featured closed and open-ended questions, unveiling the current status of museums in their pursuit of UN Sustainable Development Goals through structural changes. The results were categorized into three sections: the primary obstacles to achieving sustainable transformation, key approaches to adopting sustainable practices, and the potential benefits museums and professionals gain by implementing sustainability measures.

The responses to the survey highlight the need for an international reference that encourages the exchange of inspiring good practices. This will enable museums around the world to reorient or embark on a path toward more sustainable practices in the environmental, social, and economic dimensions.

Participants’ voices emphasize the importance of museums leading by example, respecting society, the environment, and their pivotal educational role within communities. Embracing this responsibility serves as the key driver for cultural institutions to enact positive change.

While modern and contemporary art museums are in the early stages of sustainable development, they possess a unique opportunity to establish themselves as exemplars of best practices, contributing their perspectives to global discussions on human rights, social justice, and climate-related issues.

Sustainability, rooted in universal respect for life and human

rights, demands that museums adopt this ethos as their modus operandi to the best of their abilities.

UNESCO

UNESCO has been entrusted with leading and monitoring worldwide action to deliver the targets in the

Sustainable Development Goal on

quality education for

all under SDG4. Blue

Shield, works with UNESCO.

ICOM UK

ICOM

UK is the national branch of ICOM in the United Kingdom. It is a gateway to the global museum community and the only UK museum association with a dedicated international focus. It offers access to 20,000 museums in 172 countries, 32,000 museum colleagues throughout the world and 31 professional committees.

It is an organisation which promotes intangible heritage and the preservation of material heritage. It develops best practice standards for the world- wide museum industry and, through its global reach and events programme, contributes to the international agenda of museums in the UK.

ICOM UK

ICOM UK (International Council of Museums UK) is the national branch (National Committee) of ICOM in the UK. It is a gateway to the global museum community and the only UK museum association with a dedicated international focus. As a professional membership organisation, ICOM UK supports best practice standards for the promotion and preservation of intangible and material heritage. Through its global reach and event programme, ICOM UK contributes to and supports the international agenda of museums in the UK.

BRITISH OVERSEAS TERRITORIES

ICOM UK also has a relationship with museums in the 14 countries designated as British Overseas Territories. This relationship is a valuable addition to the role of ICOM UK, bringing another important international dimension to our work.

The British Overseas Territories are:

1. Anguilla

2. Bermuda

3. British Antarctic Territory

4. British Indian Ocean Territory

5. British Virgin Islands

6. Cayman Islands

7. Falkland Islands

8. Gibraltar

9. Montserrat

10. Pitcairn Islands

11. Saint Helena, Ascension and Tristan da Cunha

12. South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands

13. Sovereign Base Areas of Akrotiri and Dhekelia

14. Turks and Caicos Islands

FOREIGN,

COMMONWEALTH & DEVELOPMENT OFFICE (FCDO)

The FCDO pursues national interests and projects the UK as a force for good in the world. It promotes the interests of British citizens, safeguards the UK’s security, defends values, reduces poverty and tackles global challenges with international partners. FCDO is a ministerial department, supported by 12 agencies and public bodies.

DEPARTMENT FOR INTERNATIONAL TRADE (DIT)

The Department for International Trade (DIT) helps businesses export, drives inward and outward investment, negotiates market access and trade deals, and champions free trade. DIT is responsible for promoting British trade across the world and ensuring the UK takes advantage of the huge opportunities open to it.

MAKING

MUSEUMS WORK

According to ICOM UK, and DIT, the UK museum sector has a world-class reputation, their skills and expertise are in demand from organisations worldwide who are looking to re-develop museums or create new institutions.

A 2013 publication by UKTI outlines some of the remarkable projects UK museums have been partners in.

NETWORK

OF EUROPEAN ORGANISATIONS (NEMO)

NEMO is an independent network of museum organisations representing the museum community of the European Member States. NEMO ensures museums are an integral part of European life by promoting their work and value to policy makers and by providing museums with information, networking, and opportunities for co-operation.

EUROPEAN CULTURAL FOUNDATION (ECF)

The European Cultural Foundation bridges people and democratic institutions by connecting local cultural change-makers and communities across wider Europe.

USEFUL

LINKS

UK Trade and Investment (UKTI)

Barrie Harris - barrie.harris@ukti.gsi.gov.uk

Richard Parry - richard.parry@ukti.gsi.gov.uk

A Different View www.adifferentviewonline.com

www.adifferentviewonline.com

Antenna International www.antennainternational.com

www.antennainternational.com

Arts Architecture International www.artsarchitecture.com

www.artsarchitecture.com

Barker Langham www.barkerlangham.co.uk

www.barkerlangham.co.uk

British Council www.britishcouncil.org

www.britishcouncil.org

British Museum www.britishmuseum.org/

www.britishmuseum.org/

Bury Museum and Art Gallery www.bury.gov.uk/index.aspx?articleid=2537

Casson Mann www.cassonmann.co.uk

www.cassonmann.co.uk

Click Netherfield www.clicknetherfield.com

Freda Matassa www.fredamatassa.com

Halahan Associates www.halahan.co.uk

Haley Sharpe Design www.haleysharpe.com

Imagemakers www.imagemakers.uk.com

ISO www.isodesign.co.uk

Malcolm Reading Consultants www.malcolmreading.co.uk

MET Studio www.metstudio.com

Science Museum www.sciencemuseum.org.uk

www.sciencemuseum.org.uk

Sun-x www.sun-x.co.uk

Turpin Smale www.turpinsmale.co.uk

Victoria & Albert Museum www.vam.ac.uk

www.vam.ac.uk

http://www.ne-mo.org/

http://www.culturalfoundation.eu/

http://www.ne-mo.org/

http://www.culturalfoundation.eu/

https://uk.icom.museum/about-us/

https://www.sustainabletourismworld.com/ecomuseum-introduction/

https://uk.icom.museum/resource/uk-government/

https://icom.museum/en/network/partners/

https://cimam.org/

https://icom.museum/en/news/sharing-is-caring-ecomuseums-and-climate-change/

https://uk.icom.museum/about-us/

https://www.sustainabletourismworld.com/ecomuseum-introduction/

https://uk.icom.museum/resource/uk-government/

https://icom.museum/en/network/partners/

https://cimam.org/

https://icom.museum/en/news/sharing-is-caring-ecomuseums-and-climate-change/

|